Energy Matching for Cooperative Robot-to-Robot Charging

I. Abstract

This project aims to optimize the social welfare of a power transfer network of a multi-robot system. The key concept is to take every robot as a unit of energy storage that can charge or discharge to each other. Thus, I define the utility for each robot based on individual energy and view this scenario as a matching problem. The Hungarian matching algorithm is applied to maximize the sum of all utilities in the multi-robot system. This report illustrates the properties (social welfare, overall energy, worker ratio, and idler ratio) of the robot-to-robot charging method. The experiment compares the traditional scenario (that all robots charge in limited charging stations) with the matching one in the Matlab Mobile Robotics Simulator. The result shows that this approach can get the better social welfare compared to the traditional method. My modification also reduces the waiting robots at charging stations by adding the negative utility of waiting behavior. However, the comparison of overall energy of the whole system between robot-to-robot charging method and the traditional one reveals the fact that this approach may suffer from energy shortage, which urges consumers to choose charging stations, as time goes on.

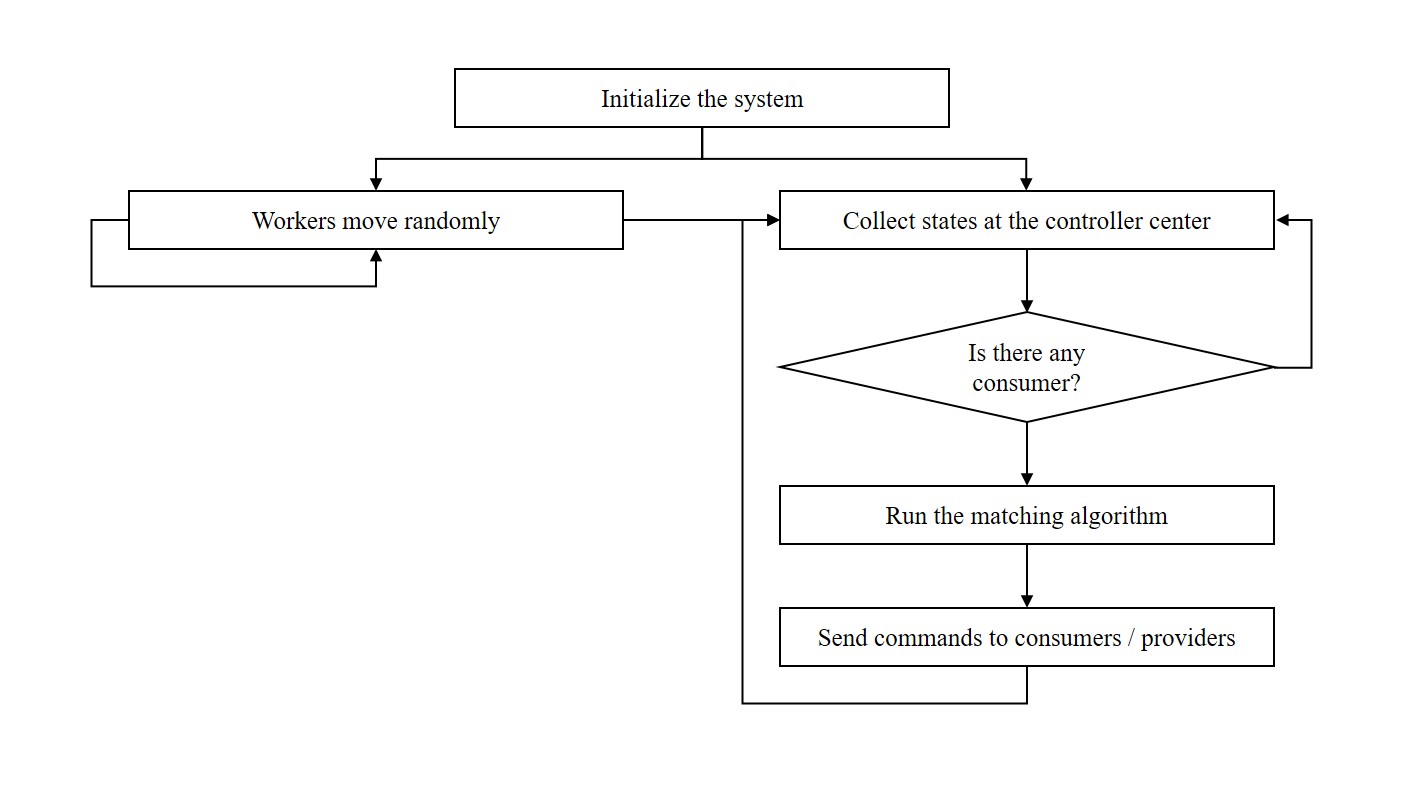

Fig. 1. The diagram of cooperative robot-to-robot changing.

II. Mathematical Model

Along with the continued trend toward accelerating the spread of multi-robot applications in warehouses, the charging issue attracts my attention. Moving a long distance to a charging station may waste energy, or waiting for a charging station reduces the overall effectiveness. Instead of optimizing the allocation of robots to charging stations, I borrow the V2V concept from electric vehicles to create a more flexible energy transfer system that enables robots to serve as consumers or providers. Viewing electric vehicles as moving batteries and applying a central controller, we can coordinate robots to realize energy transfer by collecting their status and emitting commands. Therefore, an algorithm maximizing social welfare with low computational complexity will make the matching concept more practical.

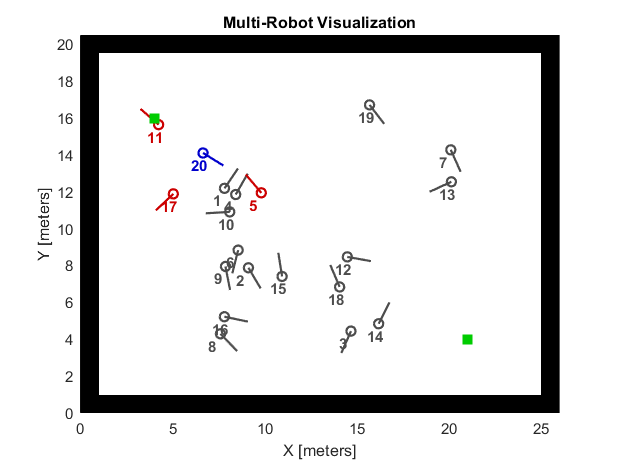

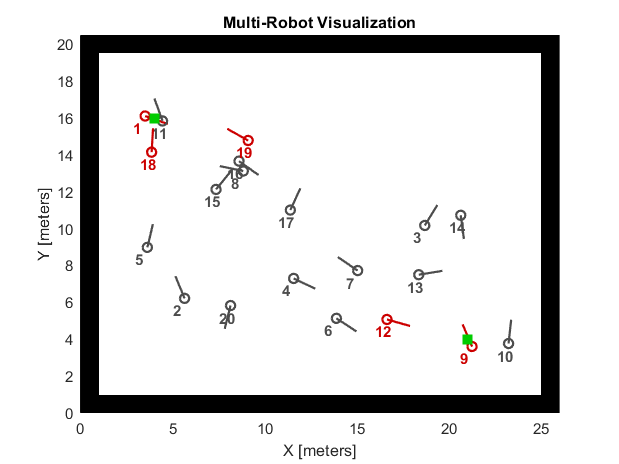

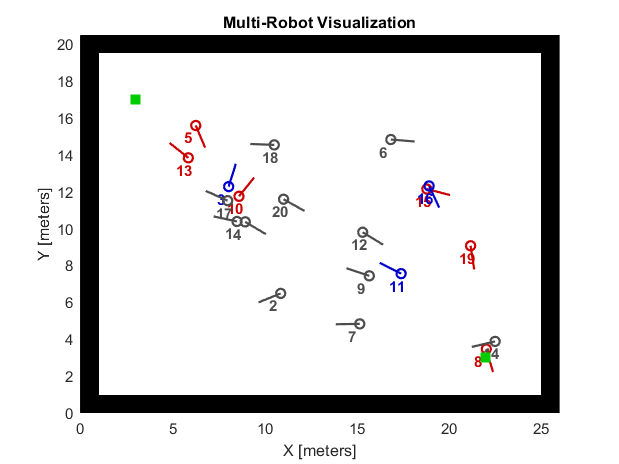

Fig. 2. Scenario visualization (robot-to-robot charging method).

III. Validation in Simulations

I compare the robot-to-robot charging method's properties with the traditional matching method in the Matlab Mobile Robotics Simulator. 10 (or 20) robots with initial energy uniformly randomizing from 10 to 100 are randomized on the map. Two charging stations sit at diagonal corners. Instead of setting charging stations to fit boundaries, I leave some space due to the limitation of the Matlab Mobile Robotics Simulator. Since the default robot model can't turn a right angle (even though I have tried to adjust the radius of wheels), it may be out of boundaries and returns an error if the charging stations sit too close to boundaries. The simulation timestep is 2,000 and I conduct 20 times of simulation to take the mean value. Fig. 2 visualizes the scenario that the red circles represent consumers, the blue circles represent providers, the gray circles represent workers, and the green squares represent charging stations. Therefore, the traditional method won’t show any blue circles. We should look into overall energy, workers, and idlers first. These properties can help us to understand the social welfare.

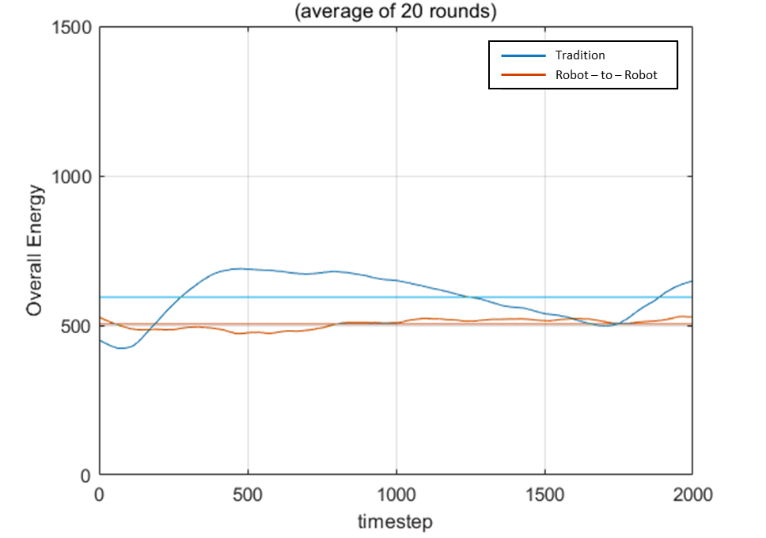

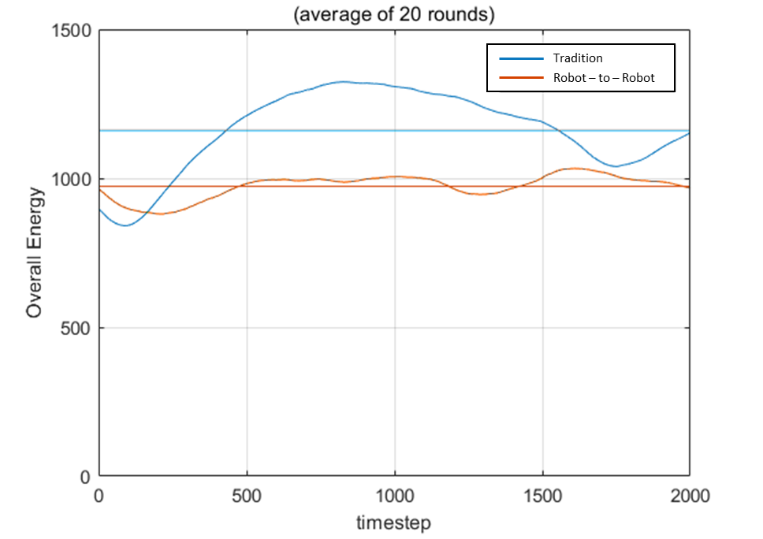

Overall energy

The result is shown in Fig. 3. It is noticeable that the robot-to-robot charging method’s overall energy is higher than the traditional one at the beginning, which is coherent with the theoretical analysis. Unfortunately, this situation only continues for a short time due to the overall energy shortage. The traditional method brings more energy to the system. The energy difference between the two methods converges as expected. Even though the number of simulation time step is not big enough for us to observe the final convergence of the traditional one, its trend appears to reach a stable state eventually.

Fig. 3. Comparison of the overall energy with 10 robots (left) and 20 robots (right)

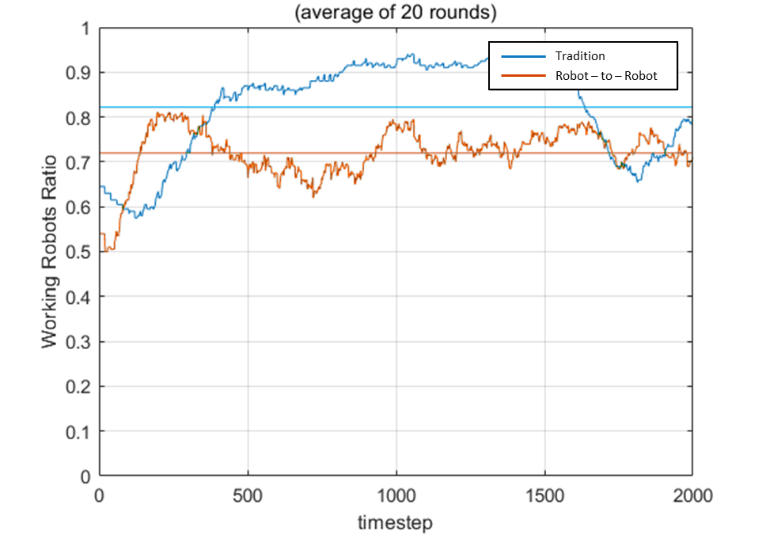

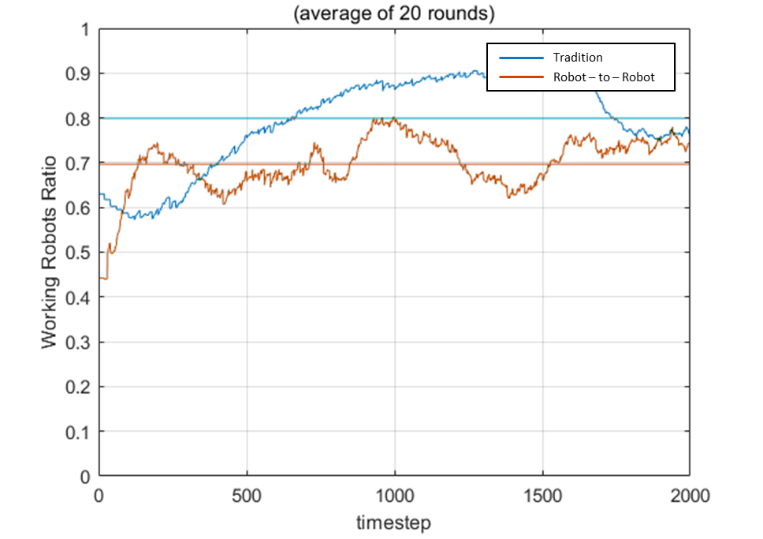

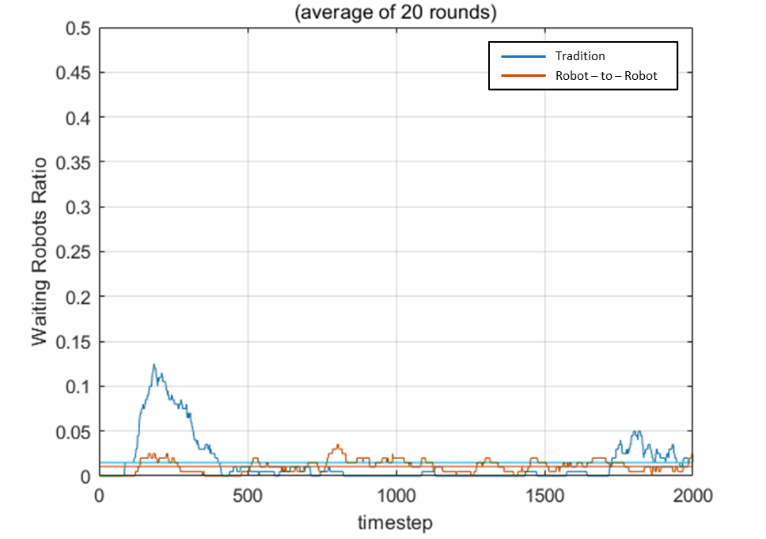

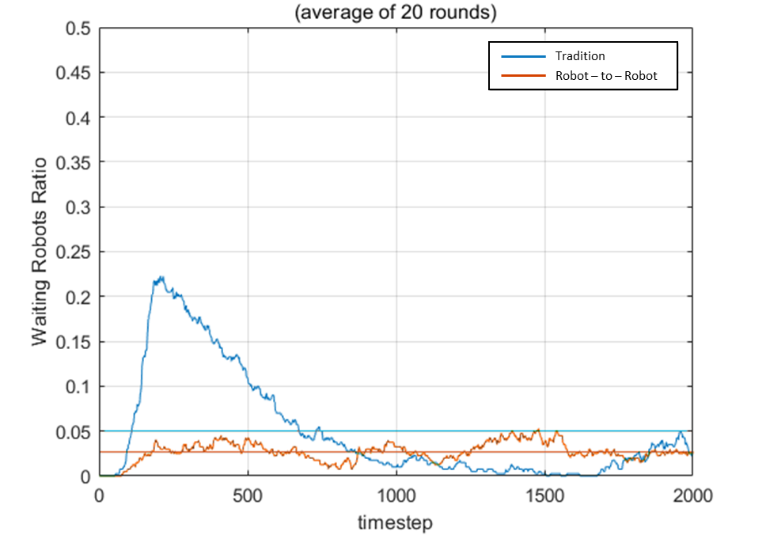

Workers and idlers

The result is shown in Fig. 4 and Fig. 5 separately. We can see that the robot-to-robot charging method has fewer workers indeed. However, the traditional method suffers from a more severe oscillation. This may cause traffic on the path to charging stations. Surprisingly, the difference of the number of idlers is not that significant no matter 10 robots or 20 robots after time goes on. This is due to the waiting time, which makes the charged robots will also come back in turn. Some conditions may cause a rush hour again. For example, if the environment is more complicated or the robots can only move on narrow aisles. This approach shows the ability to avoid heavy traffic.

Fig. 4. Comparison of the worker ration with 10 robots (left) and 20 robots (right)

Fig. 5. Comparison of the idler ratio with 10 robots (left) and 20 robots (right)

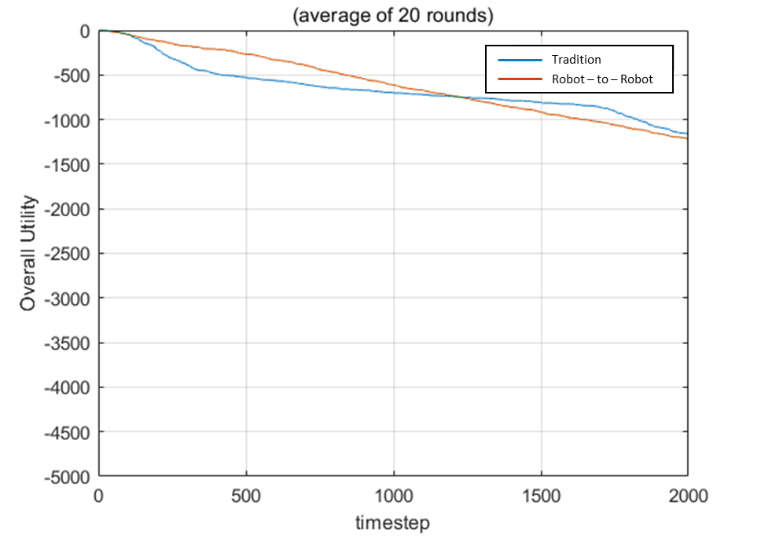

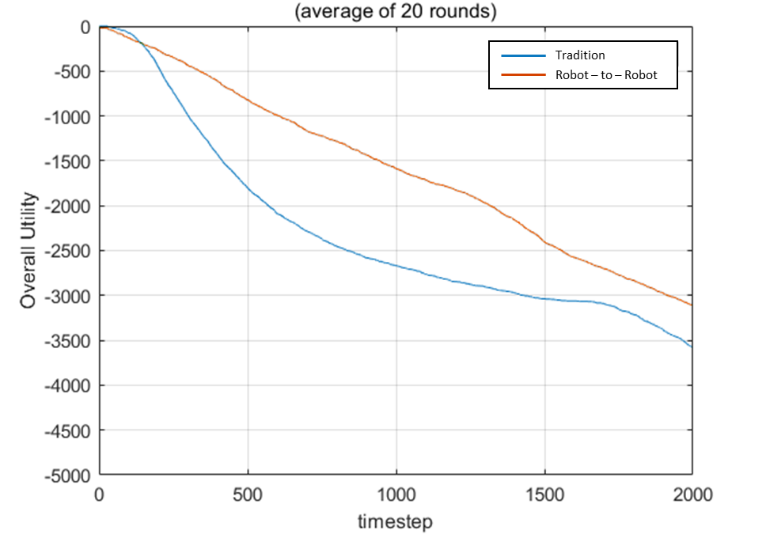

Social welfare

The result is shown in Fig. 6. Obviously, the robot-to-robot charging method brings us better social welfare as my assumption says. Notice that the declining curve is due to the energy-taking behavior from outside. The gap between the two curves is due to the negative waiting utility. Since 𝛾 is taken as value 1, the waiting behavior becomes a major factor that affects the utility. This design makes consumers tend to avoid waiting at the charging stations, and the result above demonstrates this property. The lower social welfare of the traditional method arises from all consumers waiting at charging stations. We can consider modifying the utility function so that robots can transfer energy on their working path, which may enhance efficiency. Besides, the gap distance between the two curves gets close, since the inner energy is insufficient, and all consumers have no choice but to charge stations. However, this gap distance will converge to a value after the overall energy of both methods reaches dynamic stability. The ratio between the number of charging stations and robots also matters. If the ratio is too big, the advantage of the robot-to-robot charging method will be minor since just a few consumers have to wait. If the ratio is too small, all consumers will still have to wait for charging eventually. This result also reveals that the overall energy shortage invalidates the advantage of the robot-to-robot charging method to some degree. The phenomenon makes consumers have no providers to match so the scenario will turn to the traditional one. Even so, the transferring behavior will revive if enough consumers charge fully from charging stations. Making some robots serve as couriers only may be another worthy try. There is another noticeable point that the Hungarian matching is unstable because it ignores the rationality of agents. It only cares about social welfare but ignores individual welfare. If robots have to decide which provider should match themselves, the one who brings the most valuable benefit will be considered in advance. Then we should try the Gale–Shapley matching, which is not only stable but also gets high social welfare.

Fig. 6. Comparison of the overall utility with 10 robots (left) and 20 robots (right)